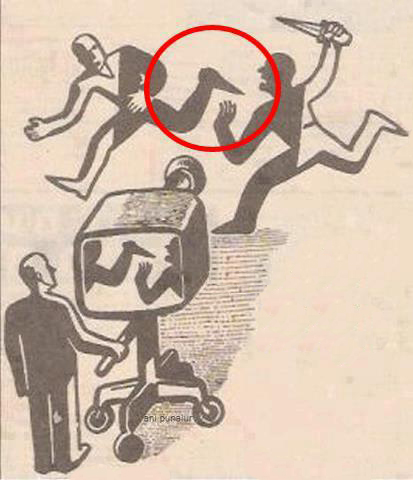

While we’re on the subject of science literacy, let’s explore the various aspects of culture that can impact the understanding of science. Why not start with the most influential of them all?

Public media reaches everyone with the message they choose, not the one you want.

If I learned anything from numerous sociology and psychology classes, it’s that it is human to have leanings that align with our beliefs. It’s quite natural that we all seek out things that we agree with and find value in. The media plays to these biases and uses them well to establish a persona and target audience. And, frankly, there’s nothing wrong with that. I talked before about biases, and it holds true to matter what media outlet you’re looking at, mass or small time. Whether we like it or not, that bias and the twists that media puts on things set us up for veritable hell trying to set the record straight if they gave people the wrong impression. (On the flip side, if they gave the right one, they can generate a lot of buzz and get the word out quicker.)

If I learned anything from numerous sociology and psychology classes, it’s that it is human to have leanings that align with our beliefs. It’s quite natural that we all seek out things that we agree with and find value in. The media plays to these biases and uses them well to establish a persona and target audience. And, frankly, there’s nothing wrong with that. I talked before about biases, and it holds true to matter what media outlet you’re looking at, mass or small time. Whether we like it or not, that bias and the twists that media puts on things set us up for veritable hell trying to set the record straight if they gave people the wrong impression. (On the flip side, if they gave the right one, they can generate a lot of buzz and get the word out quicker.)

Think it’s not a thing?

Last year, my science literacy class brought me an article from Fox News on a battle between a small time chicken farmer and the EPA. As they passed out the article for groups to look at, I heard scoffing. After all, Fox News isn’t exactly known for high calibre work when it comes to science. That view of Fox News hasn’t changed by a majority of the population, either, despite the occasional piece of good work.

So, we used this as a platform to jump into the next set of lessons: exploring bias in media sources so my students could read between the lines of the stories to find the underlying truth.

They started this off by compiling a list of places they usually turn to for news. Unsurprisingly, the list isn’t long. Most of them use Fox and CNN, a few students use BBC, and they have all learned to use Science Daily for their science fix. Only two of them use alternative sources, such as Reason.com or The Young Turks to supplement the mainline media.

After they compiled the list, they all discussed the pros and cons of each site. I asked them to find the same story on the different sites, if possible, and compare them. I asked them to look at where the news writers got their news. They discovered what many of us already know: Many articles come from Associated Press or Reuters, then the sites they look at spin them to fit their particular audiences.

After a few days of analyzing and comparing all the Web sites, I had them list the biases that were readily present in their favorite Web sites as well as those they dislike. This stung many of them, and they clung stubbornly to the “I’m right, you’re wrong” mentality for quite a while. Eventually, though, they began to see how each media sites they chose was biased, and to what degree.

It was only then that we got down to a discussion on why they looked at these sites. The consensus as summarized by the class: “They are easy to understand (in terminology and language) and they feel “friendly” (meaning they align with the individual’s personal biases).”

I had them look again at the Fox article and had them also look at the Bay Journal article which discussed the EPA debate of the previous week. We worked together to create a list of the things that showed the biases, and I asked them to give a “percentage” on how much they felt it was biased on that particular point. It’s no surprise that they found Fox to be highly biased, and even a touch unfair.

To get past the biases, people need to learn to look harder at their sources as well as read between the lines.

One of the students wanted to know if any other sources had picked it up yet to put a different spin on the case. I was impressed that they would grasp the idea of looking at a myriad sources so quickly, so we did a quick Google and Bing search to find out if there were any new, related articles. We were all disappointed that the only mainstream news agency to pick it up was Fox, and unsurprised that several farming-oriented news sources would be the majority of the articles.

I asked the students if this information helped change their mind about the EPA, as they had decided in the last week. They surprised me by asking for more evidence, especially about the outdated data being used in their models. With lessons like these in the world of science literacy, I have hopes that people will start to see science in the media differently, start asking questions, and not be so quick to judge harshly. It is, after all, a part of really understanding the science behind the actual news.

When it comes to communicating your work, beware that this could be a potential problem. Plan for it by doing your own PR on your work (or having it done for you) before it gets twisted into something that is just a shade of the truth.