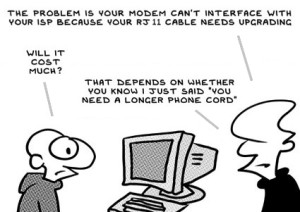

Admittedly we could all stand to learn a little more precise vocabulary. Found @ Technofaq.

How does this sound to you: We will transition integrated articulation to close the achievement gap.

Or this? We will agendize multidisciplinary explicit direct instruction within professional learning communities.

This is what we call bullshit jargon. It’s a word salad of impressive sounding syllables thrown together in attempt to amaze. Frankly, though, it just makes eyes glaze over. And, these phrases don’t mean a damned thing.

Last year John Besley, associate professor in the Department of Advertising and Public Relations, received a $310,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to study how scientists can become better communicators by studying how scientists both view and communicate with the public. This question is solid, but also a perfect example of how scientists think.

The Land of Science is precise.

We spend time finding the most accurate way to state what we are doing, thinking, and working on. It doesn’t necessarily have to make sense to others, as long as we are using the full extent of our vocabulary to say exactly what we mean. It is also a way to show off our intelligence to one another. It’s a banner that screams to the ears of the other person, “I know what I’m talking about, and I belong!”

Sometimes when people get so wrapped up in their own world, they forget to come out of it again. For example, I often use the word “adsorb“. It’s a simple concept in chemistry where a substance forms a molecule thick film on a solid. People were too lazy to look up this word in a dictionary, and I certainly wasn’t going to put this in every paper I wrote on the subject to non-chemistry people. So, I just stopped writing things for non-chem majors for a time. It was just easier on me that way during the time I was in school. Once we’re in this world, though, we stop thinking about the non-specialised person out there that has no idea what our words mean — even if they’ve taken the introductory course.

This is problematic.

Everyone feels it. Found @ Balmung6’s Deviant Art.

It doesn’t matter if you are going to stay in academia or if you’re transition out to a life of your choosing. Being able to speak both to your cronies in your field and the general public has its advantages. You see, in the post sequestration, scientists have had to learn to navigate the environment and their craft more efficiently and persuasively. A tough thing to do for sure when they are used to exploration without a tangible, profitable goal of any sort.

Science for the sake of science is a luxury that we have gotten used to, but when the government had to tighten their spending in many areas, this was one thing they had to shake their head at. It would be like indulging in hot chocolate every night when what you really need is reliable nutrients. When push comes to shove, you have to make sacrifices in order to make ends meet.

This, unfortunately, is what we have to deal with at the moment. Some have chosen to run away to a country where they could still be pampered while they practise their craft, while others have decided to take a different route; they practise low-tech, high science techniques at their kitchen table. Is this enough though?

Yes, in fact, it could be. Kay Aull and Meredith Patterson are showing that it can work with a little bit of an open mind.

Kay Aull grew concerned about her genetic potential to develop a fatal liver disorder that runs in her family. Instead of spending thousands of dollars to have her genes analysed, she decided to build her own lab — in her bedroom closet — and do it herself for a pittance. And from there, her ideas blossomed into one of the smallest full-fledged synthetic biology laboratories in the world.

As for Meredith Patterson, she took it upon herself to develop a relatively inexpensive test to see if there is melamine in milk using ingredients you can find in your kitchen. How? With the Promethean model of innovation: bravely storming the mountain where knowledge is shrouded in peril. And a few ziplock bags scattered around her kitchen table.

The thing is, all of these low-tech methods scare the ever-living shit out of people. So, the makers and doers talk to the public, teach them, and make their work open source. This helps alleviate fears, gets people excited, and in the case of crowdfunded projects, even gets people donating money to see the end product sooner.

Science doesn’t have to be expensive. It shouldn’t be shrouded in mystery and peril, either. We should place an emphasis on increased science literacy for everyone, including people in Congress. Perhaps if they could understand us they would understand the importance of our work.