Picture this: You’re watching a student’s eyes light up as they use a pulley system to effortlessly hoist a heavy bucket. “This machine takes away work!” they exclaim triumphantly. You smile—they’re engaged, they’re excited—but there’s a problem. They’ve just locked in one of the most persistent misconceptions about simple machines, one that will muddy their understanding of physics for years to come.

As educators, parents, and mentors guiding young scientists, we know that hands-on demonstrations aren’t enough. The real magic happens when students grasp the why behind what they observe. Yet three stubborn misconceptions about simple machines trip up learners at every grade level, and if we’re not careful, our teaching can accidentally reinforce these errors instead of correcting them.

This article clears up the confusion about “machines give you more work,” force versus distance trade-offs, and what “mechanical advantage” really means. We’ll use ramps and pulleys as our primary examples—two simple machines you can explore with minimal equipment but maximum impact. By the end, you’ll have the conceptual clarity and practical teaching strategies to position yourself as strong on understanding, not just “cool demos.”

Misconception #1: Simple Machines Take Away Work (Or Reduce the Work You Have to Do)

The Mistake

This is perhaps the most common and damaging misconception, often introduced in elementary school with well-intentioned but imprecise language. Students hear that machines “make work easier” and leap to the conclusion that machines reduce the total amount of work required. After all, if pushing a refrigerator up a ramp feels easier than lifting it straight up, surely the machine is doing some of the work for you, right?

Wrong.

The Reality

Here’s the principle that governs every simple machine ever created: Machines do not—cannot—decrease the amount of work you have to do. This isn’t a limitation of current technology or a design flaw. It’s a fundamental consequence of the law of conservation of energy .

Work, in physics, is defined as force multiplied by distance (W = F × d). When you use a simple machine, the total work input must equal the total work output (minus losses to friction and heat). A machine cannot create energy from nothing; it can only redistribute how you apply that energy .

So what does “make work easier” actually mean? Simple machines change how it feels to do work by allowing you to apply a smaller force—but you must apply that smaller force over a longer distance. The trade-off is precise and unforgiving: cut the force in half, and you must double the distance. Reduce the force to one-third, and you triple the distance .

When introducing simple machines, language matters enormously. Instead of saying machines “reduce work” or “take away work,” be explicit:

-

“Machines redistribute work by changing the relationship between force and distance”

-

“Machines let you trade distance for force, or force for distance”

-

“The total work stays the same; what changes is how you apply it”

Hands-on verification: Have students measure both force and distance when lifting an object directly versus using a ramp. Calculate work in both scenarios (W = F × d). When done carefully, students discover that the work values are nearly identical—with any difference attributable to friction. This concrete evidence is far more powerful than any verbal explanation.

Misconception #2: The Force-Distance Trade-Off Is Optional or Negotiable

The Mistake

Even students who grasp that machines don’t reduce total work often miss the iron-clad relationship between force and distance. They might understand that a pulley reduces the force needed to lift something, but they don’t connect this reduction to the requirement that they must pull more rope. Or they recognize that a gentle ramp requires less pushing force than a steep one but fail to see the necessary consequence: the gentle ramp is longer, requiring the object to travel a greater distance .

The Reality

The force-distance trade-off is not a suggestion—it’s a mathematical necessity arising from energy conservation. When one variable decreases, the other must increase proportionally to keep work constant .

Consider a concrete example with a ramp:

-

Lifting a 100 N object straight up 1 meter requires: W = 100 N × 1 m = 100 J

-

Pushing the same object up a 2-meter ramp to the same 1-meter height requires: W = 50 N × 2 m = 100 J

Notice what happened: by doubling the distance (1 m to 2 m), we cut the force in half (100 N to 50 N). The work remained exactly 100 joules.

This inverse relationship applies to every simple machine:

-

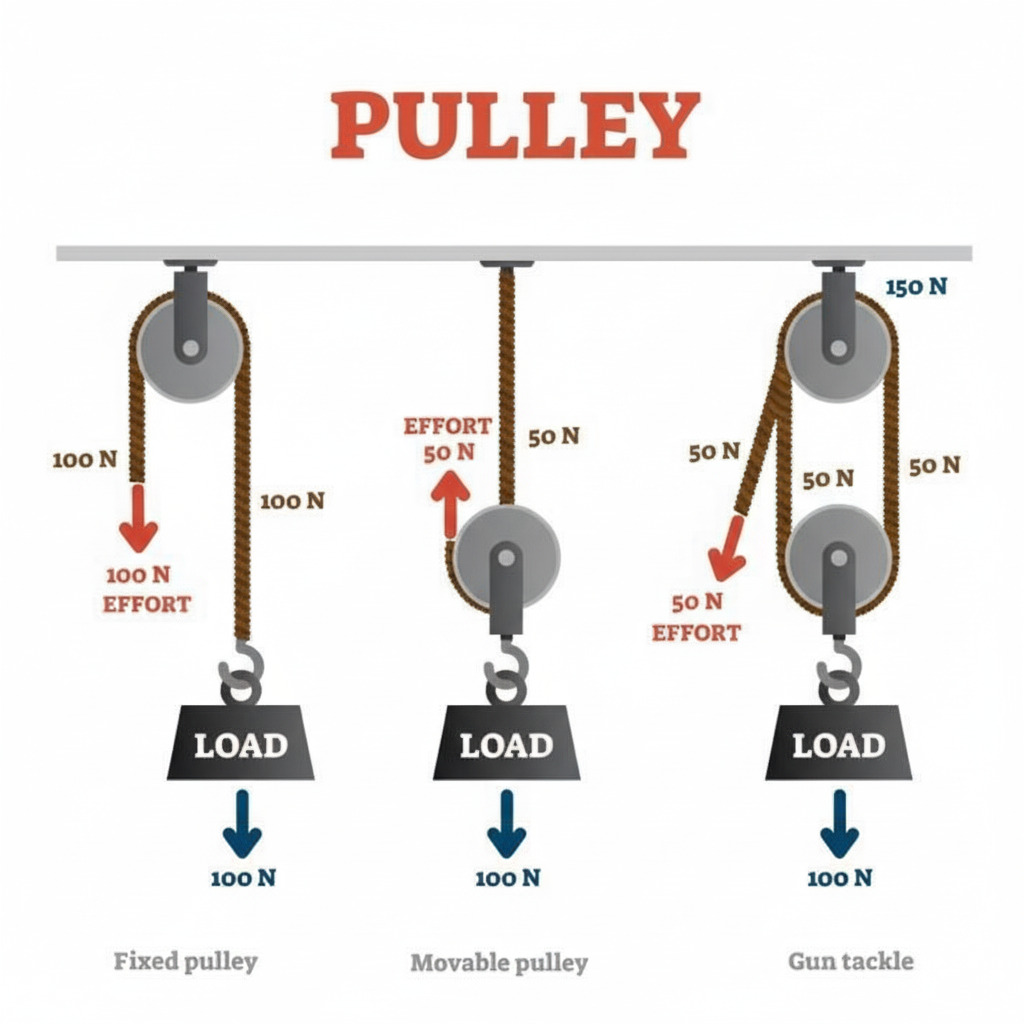

Pulleys: A 2:1 pulley system cuts the effort force in half but requires pulling twice the length of rope

-

Levers: Moving the fulcrum to increase leverage (reducing effort force) necessarily increases the distance the effort side must travel

-

Inclined planes: Making a ramp gentler (reducing force) makes it longer (increasing distance)

Help students see this trade-off in action rather than just calculating it:

Ramp Activity: Set up ramps at multiple angles (steep, medium, gentle). Have students use a spring scale to measure the force required to pull a cart up each ramp while also measuring the length of each ramp. Create a simple table showing that as ramp length increases, force decreases—but the product (work) remains roughly constant.

Pulley Activity: Build three pulley configurations: direct lift (no pulley), single fixed pulley, and movable pulley. For each system, have students:

-

Measure the effort force using a spring scale

-

Measure how much rope they pull to raise the load a specific distance (say, 50 cm)

-

Calculate work for each scenario

Students will discover that while the movable pulley cuts effort force in half, they must pull twice as much rope. Once again, work is conserved.

Discussion prompts:

-

“What do you notice about force when distance increases?”

-

“Can you design a simple machine where both force AND distance decrease?” (No—this would violate energy conservation)

-

“Why might you choose a machine that requires more distance, even though it seems less convenient?” (Physical limitations on force you can apply; think wheelchair ramps)

Misconception #3: “Mechanical Advantage” Means You Do Less Work

The Mistake

The term “mechanical advantage” sounds like you’re getting an advantage in the amount of work you do. Students (and sometimes adults) hear “advantage” and think “less work total” or “free energy”. This misconception is reinforced when we talk about machines “multiplying force” without clarifying what’s being traded away.

The Reality

Mechanical advantage (MA) is simply the ratio of output force to input force :

MA = Output Force ÷ Input Force

That’s it. Mechanical advantage tells you how much the machine multiplies your force, but it says nothing about reducing total work.

A machine with MA = 3 means:

-

Every 1 newton of input force produces 3 newtons of output force

-

BUT: You must apply that 1 newton over 3 times the distance the load travels

-

The work input still equals work output (minus friction)

Let’s break this down with a pulley example :

Movable pulley system (MA = 2):

-

You pull with 50 N of force (input force)

-

The pulley system delivers 100 N to the load (output force)

-

Mechanical advantage = 100 N ÷ 50 N = 2

-

To raise the load 1 meter, you must pull 2 meters of rope

-

Your work = 50 N × 2 m = 100 J

-

Load work = 100 N × 1 m = 100 J

-

Work is conserved; you simply traded distance for force

The advantage is that you can lift a load too heavy for you to lift directly. The disadvantage is that you must pull rope over a much longer distance. You’re not getting extra work out of the system—you’re reconfiguring the force-distance relationship to match your physical capabilities or practical constraints .

Ideal vs. Actual Mechanical Advantage

To deepen student understanding, introduce the distinction between ideal and actual mechanical advantage:

Ideal Mechanical Advantage (IMA): The theoretical MA calculated from distances, assuming no energy losses:

-

IMA = Input Distance ÷ Output Distance

-

For a ramp: IMA = Length of Ramp ÷ Height

-

For a pulley: IMA = Number of supporting ropes

Actual Mechanical Advantage (AMA): The real-world MA measured from forces:

-

AMA = Output Force ÷ Input Force

-

Always less than IMA due to friction, rope bending, pulley bearing resistance, etc.

Efficiency: The percentage of theoretical advantage you actually achieve:

-

Efficiency = (AMA ÷ IMA) × 100%

-

Always less than 100% in real machines

This distinction helps students understand why their measured results never quite match theoretical predictions—and introduces the real-world engineering challenge of minimizing friction and maximizing efficiency .

Vocabulary precision: When introducing mechanical advantage, explicitly state:

-

“Mechanical advantage tells us how much the machine multiplies force”

-

“A higher MA means less force required, but more distance to cover”

-

“MA does NOT mean less work—work is always conserved”

Your students gathered around a simple pulley setup, experimenting rather than following a strict recipe. They start by trying out both fixed and movable pulleys, noticing how each one “feels” different as they lift the same load. With a spring scale, they jot down the force they pull with and compare it to the weight of the load, then turn those numbers into actual mechanical advantage by dividing output force by input force. As they get more curious, they begin measuring how far they pull the rope versus how far the load actually rises, using those distances to work out the ideal mechanical advantage and, from there, the efficiency of each system. Along the way, they see for themselves that the real-world advantage is always a bit lower than the ideal, which naturally leads into questions about friction and where the “lost” energy goes. You might close by tossing out a thought experiment—could anyone really build a machine with infinite mechanical advantage?—and let students wrestle with why making the input force tiny would mean stretching the input distance toward infinity, with time, space, and friction quickly getting in the way. If you want to take this further without adding to your prep load, you can fold this activity into the simple machines mini‑unit we’ve developed, which already includes vocabulary cards, equations, and student prompts that plug right into this kind of exploration.

Why These Misconceptions Matter

You might wonder: does it really matter if students think machines “give them more work” as long as they can operate the machines successfully?

Yes, it matters profoundly.

These misconceptions don’t just muddy students’ understanding of simple machines—they undermine their grasp of fundamental physical principles that govern everything from electric motors to hydraulic systems to the human body. Students who believe machines can create energy from nothing will struggle with:

-

Conservation of energy: If machines can give you “free” work, why do we worry about energy efficiency?

-

Power and efficiency: Understanding why no machine operates at 100% efficiency requires grasping that all machines lose some energy to friction

-

Engineering design: Engineers must quantify trade-offs between force, distance, speed, and energy—skills that start with simple machines

-

Critical thinking about pseudoscience: The persistent belief that machines can output more work than input feeds into “perpetual motion” myths and other scientific misconceptions

Moreover, when students learn incorrect physics principles early, these misconceptions calcify and become progressively harder to correct. Research on student misconceptions consistently shows that alternative conceptions formed in elementary school persist through high school and even college-level physics courses. The time to build correct conceptual foundations is now, when students first encounter these ideas .

Practical Strategies For Teaching Simple Machines

Start with leading from principle to example. Open units by emphasizing that energy is conserved and that simple machines only transform how we apply that energy. Then frame activities around the question, “How does this machine redistribute the work rather than reduce it?”

Make measurement central so students can tell the difference between “feels easier” and “is less work.” Have them measure forces, distances, and calculate work in different setups, then compare values to see that work stays roughly the same.

Build in comparison activities to make the force–distance trade-off impossible to ignore. For example, use the same object on ramps of different angles, or lift the same mass by direct lift, fixed pulley, and movable pulley, and have students compare their data.

When you talk about mechanical advantage, emphasize why we choose different setups. Ramps trade distance for lower force so human muscles can handle the job, and sometimes we even want MA < 1 because we’re trading force for more distance or speed instead.

Finally, make it normal to surface and fix misconceptions. Ask what students think will happen, let the measurements challenge those ideas, and guide them toward the conclusion that machines trade force and distance but never reduce the total work. Everyday examples—wheelchair ramps, loading ramps, cranes, elevators, bicycle gears—anchor this understanding in real life without needing a long treatment inside the post.

Looking for more hands-on science activities that build conceptual understanding? Get the free resources within the Resource Library (password in available to email subscribers) area or dive head first into the mini unit.