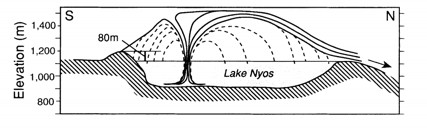

On August 26, 1986, the normally tranquil, blue water of Lake Nyos in the West Africa country of Cameroon unexpectedly turned deadly. Late that night, according to the few people who survived to tell the tale, a low, rumbling sound emitted from the lake. The residents of the three villages on the shores of the lake stepped outside to investigate and saw a tall plume of water from Lake Nyos. What they didn’t know, unfortunately, was that toxic gas was accompanying the fountain of water. That night, 1,746 people around Lake Nyos died from breathing carbon dioxide. How could an ordinary lake suddenly turn violently deadly? The answer is a rare natural phenomenon called limnic eruption, otherwise known as lake overturn.

A limnically active lake is a body of water located near volcanos. The volcanic action releases carbon dioxide, or CO2, into the lake bottom through fissures. The CO2 is trapped in the deepest levels of the lake, held down by the warmer layers of water. If the water saturated with carbon dioxide were to stay in place on the lakebed, there would be no problem. The limnic eruption occurs when the different layers of water in the lake are disrupted.

The water layers of a limnically active lake can be displaced due to a number of reasons, including seismic or volcanic activity. The investigation into Lake Nyos revealed that a landslide sparked the explosion when rocks pierced through to the bottom layer and displaced the water.

The Lake Nyos disaster in Cameron wasn’t the only time lake overturn killed residents of the country. Two years prior to the Lake Nyos disaster, another lake in the region, Lake Monoun, experienced the first recorded limnic eruption. This 1984 event killed 37 people on the shores of the lake, to the puzzlement of authorities. There were strange, burn-like blisters all over the bodies of the victims. When they interviewed survivors, they were told an unbelievable story about a low-hanging white cloud with a foul smell that emanated from the water and hugged the ground. The initial theory was that the deaths were the result of intentional poisoning or the release of a chemical weapon.

It was a scientist from the University of Rhode Island who solved the mystery of the Lake Monoun deaths. Haraldus Sigurdsson, a member of the team of researchers sent to Cameroon at the request of the United States government, was quickly able to determine that chemical weapons were not to blame. Sigurdsson determined that the water of the lake contained CO2 and that the water at the bottom of the lake had a much higher concentration of the deadly gas. The cause of the deaths at Lake Monoun was attributed to limnic eruption. The much more catastrophic lake explosion at nearby Lake Nyos two years later served as a real wake-up call for the region.

Subsequent studies at all of the lakes in the region discovered another lake, Lake Kivu, a body of water that straddles the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, that was at risk for an explosion. While Lake Kivu is quiet now, research of the area shows that it wasn’t always calm. University of Michigan’s researcher, Robert Hecky, studied soil and sediment samples from around Lake Kiva. His findings suggest that a mass casualty event took place at the lake at least one roughly every one thousand years. Fossilized remains of large amounts of animals reveal high concentrations of carbon dioxide. In addition, the evident indicated that vegetation also died in a large area surrounding the lake.

The Rwandan government took the threat seriously, perhaps because the lake is two thousand times larger than Lake Nyos and because more than two million people live in close proximity to the shores of the lake. They launched an initiative to prevent a limnic explosion at Lake Kivu.

The solution to the problem was deceptively simple. We have all had experiences opening with a soda bottle that has been shaken. You could completely open the bottle, but if you do, the built-up pressure will release in a sudden explosion of soda. Typically, what we do is to open the bottle slowly, a little at a time, to release the pressure. Visualize the lake as a soda bottle that has been shaken. It has built up a lot of pressure and is just waiting for something to open it up so that it can release the pressure. Like the soda bottle, the key to keeping limnically active lakes stable is to release the pressure slowly and safely. But how?

In Lake Nyos, authorities, led by French scientist Michel Halbwachs, have inserted pipes into the water that extends down to the lake floor. The carbon dioxide seeps out of the pipe at small, safe levels that are enough to prevent the pressure from building up at the bottom of the lake. People living around Lake Monoun followed suit. Scientists continually monitor the lakes and inspect the pipes to make sure that the CO2 levels remain at a safe, non-explosive level.

A similar program is being implemented at Lake Kivu, but here, the scientists are planning to turn the potential disaster into a benefit. Unlike Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun, Lake Kiva’s explosive pressure is caused by a build up of methane gas. A program, called KivuWatt, aims to use pipes to relieve the lake pressure, just as is done in Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun. But instead of allowing the gas to escape into the air where it can dissipate, the KivuWatt project plans to capture the methane gas and use it as an energy source. The once-deadly lake could provide electricity for the people living on its shores.

Lake overturn, or limnic eruption, is one of the rarest natural disasters on earth. To create the deadly force, all the conditions must be just right, therefore it only occurs in a few bodies of water. What the Lake Nyos disaster has taught researchers is that there are still natural phenomenons that we don’t totally understand, but with careful study, we can unlock their secrets and make these once-dangerous areas safe for human habitation.

Sources:

“Lake Nyos: Silent But Deadly.” Volcano World, Oregon State University, volcano.oregonstate.edu/silent-deadly.

National Geographic Society. “Lake Turnover.” National Geographic Society, 9 Nov. 2012, www.nationalgeographic.org/media/lake-turnover/.

“Scientific Scribbles.” Scientific Scribbles, University of Melbourne, 25 Aug. 2012, blogs.unimelb.edu.au/sciencecommunication/2012/08/25/exploding-lakes/.

Whitehead, Frederika. “The Killer Lake: How an Exploding Lake Became a Gold Mine for Rwanda.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 6 Feb. 2015, www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/feb/06/killer-lake-kivu-gold-mine-rwanda.