A recent worry I’ve heard from some of our homeschoolers and independent scientists alike is how to do research successfully from the comfort of their home. You’d be surprised to know that a great deal of science and research can be done from home provided you pay attention to laws and regulations.

I beg you to reconsider.

I do chemistry regularly at home. Seriously.

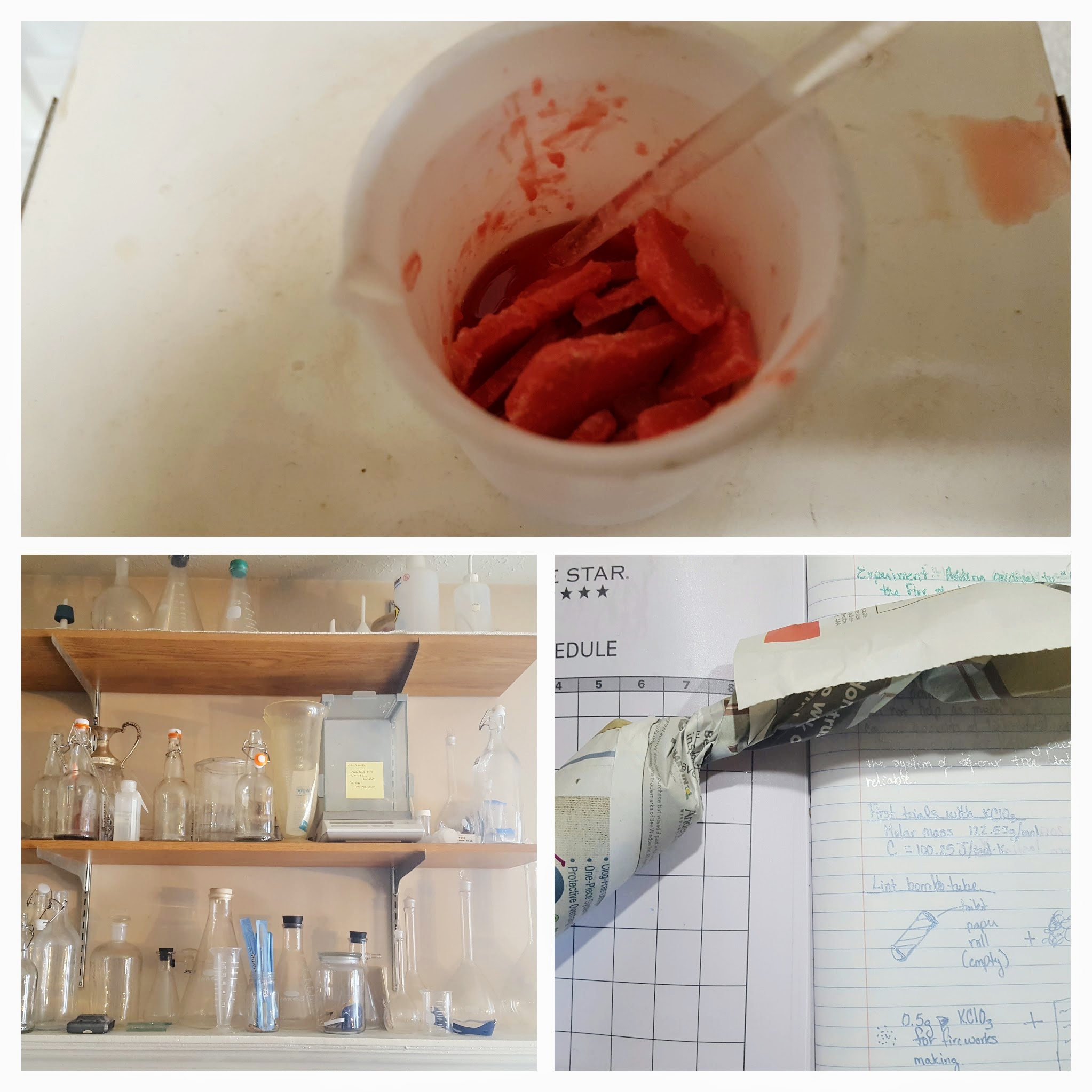

The collage to the left is just what I’ve been working on this past week. My glass collection I got from eBay, specifically from Hershel of PapaMed4 since he comes to Indianapolis where I’m at, and if I need anything in a hurry I can trust he will get it to me through the mail with no breakage. Not to mention his prices are pretty reasonable, if not a downright steal.

The rest is work for two types of lint firestarters I’m working on. One type is a simple lint and wax starter. The questions for that experiment are: 1.) What ratio of wax and lint works best and 2.) is there a significant difference between wax types? Trial and error — and plenty of warm fires will tell.

The second lint firestarter experiment involves small amounts of potassium chlorate (KCLO3) used as an oxidiser when we put the firestarter in the middle of the logs. KCLO3 is used in commercial creosote logs. These are legal, so it follows that our firestarters are legal. What may be questionable is the storage of the KCLO3 so we keep it at a relative’s place in a fireproof storage cabinet.

But chemistry is chemistry… what about other sciences?

Ever hear of Biopunk? It’s not just a book or science fiction genre, but it’s also a type of science that has many gatherings around the world. It’s biology…. in the kitchen. Or closet. Wohlsen collected bioscientists stories to show you what can happen when you put your mind to it. I, personally, don’t know anyone in this sphere, but Wohlsen introduces the readers to the likes of Kay Aull, who built a genetic testing kit in her closet.

Ever hear of Biopunk? It’s not just a book or science fiction genre, but it’s also a type of science that has many gatherings around the world. It’s biology…. in the kitchen. Or closet. Wohlsen collected bioscientists stories to show you what can happen when you put your mind to it. I, personally, don’t know anyone in this sphere, but Wohlsen introduces the readers to the likes of Kay Aull, who built a genetic testing kit in her closet.

If genetic testing isn’t your thing, perhaps you’d be more interested in perhaps DIY drug developments like Andrew Hessel, or testing milk for poisons like Meredith Peterson is more your thing.

The point, of course, is that if you think science is elusive and can’t be done in your garage — you’re fortunately mistaken.

The inspiring stories in Biopunk were actually what inspired me to do chemistry from home, even as I trained as I trained young children through the museum with more simple DIYs that explained the basics of each field of science.

What would you create?

The key to taking science from a DIY level to something that truly changes the way you work with the tools is a true science literacy. It starts with asking the key questions: what, why, how, so what — along with the most important what if. What if I freeze the glue before making slime balls? What if we used thicker rubber bands for racing balsa cars?

Ask the what if — then ask why the result happened. Start diving into the deeper science of it to really understand what is happening in front of you.

Once that’s comfortable, the next step is to ask how to get things to a level of your design. How can you get bottle rockets higher? How do you make kitchen potato clocks last longer? How is the first step to embracing science and making things of your own design to your needs. This also includes the what question. What, exactly, will get you what you need? A short-lived potato clock might work for someone if they are baking one item, but what if they need it to last through the holiday season? Being willing to explore these questions is where the scientist is born.

Taking your kitchen to the next level

If I might be frank about being an academic for a second, I’d like to admit something that we usually keep to ourselves.

We have no clue what we’re doing most of the time. When we’re undergrads, we think we know everything. When we’re floundering around in our master’s studies, we realise we know absolutely nothing of consequence. By the time we reach our doctorate studies, we finally come to grasp with it (usually around the time we realise that we passed our thesis defence), and start regaining confidence in our field again. Then, we look around at the other fields and think, “Well, I might not have a bloody clue what that chap just said, but I’m smart enough to catch on quickly.” And we do.

Along the way we learn industry knowledge and skills. Machines break, and we stare at it bewildered for a moment before either crying for help or grabbing the manual and diving in. We get used to failure when things just don’t work. We’re used to results we didn’t expect and scratching our heads wondering if it was supposed to be that way — of if we mucked up along the way.

The secret is learning to ask a lot of questions and figuring out the answers. Anyone can do that — the only difference between a professional lab and your kitchen is the type of equipment.

Need more inspiration? Check out Josiah Zayner story below.