Original author: Karen Harris

As far a microorganisms go, yeast is a good guy. It has long been an ally of humans, perhaps as far back as 5,000 years. Yeast is responsible for initiating a chemical reaction that causes bread dough to rise, giving bread a lighter texture and an improved taste. But 5,000 years ago, when the ancient Egyptians developed the bread making process, yeast was an essential, yet unknown, component. In fact, the ability of yeast to make bread dough rise was considered “magical” and even a “gift from the gods”…gods who apparently wanted the Egyptians to carb up. The understanding of microbiology and the complex process of microbial chemistry was still centuries away. Therefore, without their knowledge or intent, the people of ancient Egypt utilized man’s first industrial microorganism.

Yeast is a living organism which is classified as a member of the Fungi kingdom. Yeast metabolizes sugar, found in small quantities in flour, and ethanol and carbon dioxide are released. This is the fermentation process. Carbon dioxide bubbles expand, causing the dough to rise. A complex combination of gluten, found in the wheat flour, along with lipids and proteins form a chemical structure than prevents the carbon dioxide bubbles from dissipating. When the dough is baked into bread, the carbon dioxide escapes and leaves behind the hollow gluten/lipids/protein structures that make the bread light and airy, rather than dense and thick.

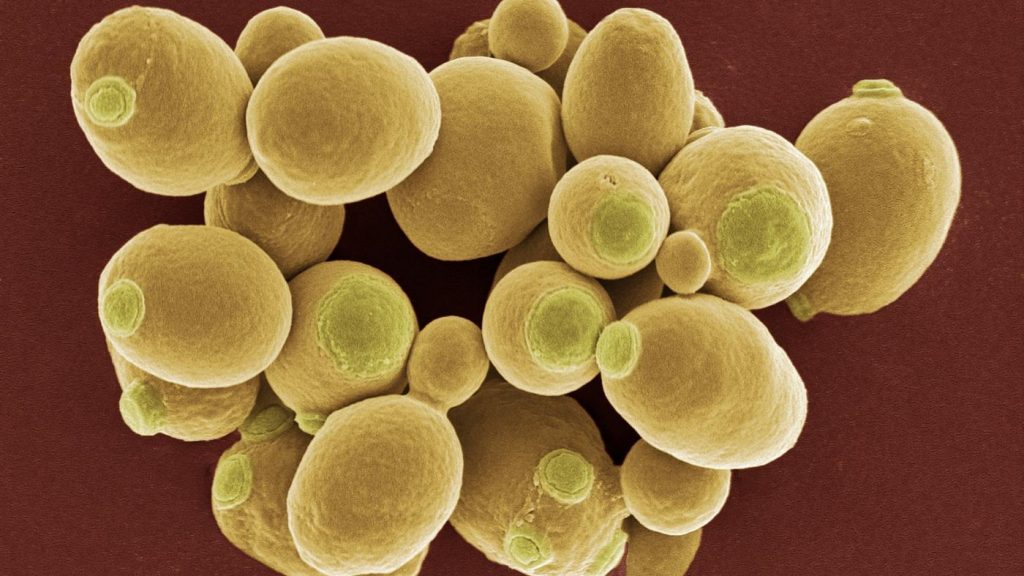

Yeast microbes multiply rather easily by budding and grow by feeding off the sugars in flour. Ancient bread makers were able to ensure that the fermentation process continues –even if they didn’t understand it – by saving small portion of bread dough to use as a “starter” for the next batch. By adding this starter to a fresh bowl of flour and water, the yeast organisms could continue to grow and multiple. In this way, ancient people were able to keep producing light and spongy bread. Another way they did this was by adding the frothy heads from the beer-brewing process, which also utilized grains and fermentation, to their bread dough.

Scientists believe that the wheat and other grains used in bread making in ancient Egypt became contaminated with naturally-occurring yeast organisms. There are, so far, about 1,500 identified varieties of yeast. With so many yeast varieties out there, it is easy to see how a contamination could occur. Lucky for us that it did. The addition of yeast and the fermentation process to bread baking greatly improved the food item, taking it from a humble staple of life to the tasty favorite and extremely versatile food that it is today.

We need to fast forward from ancient Egypt to 1680 Netherlands to learn the next step in the rise of yeast. This is when the noted Dutch scientist, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who had developed an interest in lens making, used his home-made microscopes to observe microbial life in his beer. A self-educated scientist, Van Leeuwenhoek’s work helped to establish the discipline of microbiology and led him to become known at the “Father of Microbiology”. But it would take several more decades before we would truly understand the mechanism of yeast.

Our next stop is 1857 France where Louis Pasteur discovered that the microorganisms called yeast were responsible for the fermentation process in baking and brewing. Pasteur was able to show, through numerous experiments, that fermentation results from the action of yeast, a living microscopic organism, in converting glucose in flour into ethanol. He was also able to prove that yeast had to be alive in order to metabolize the glucose. His work was instrumental in enabling people to isolate the yeast strains in pure form in. This ability allowed for the commercialization of yeast. Within a few years, companies sprung up to grow and sell dried or caked yeast, most commonly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for use in the baking and brewing industries.

A happy accident of wheat contamination by yeast microorganisms in ancient Egypt was instrumental in elevating bread making to an art form which, in turn, gave us an array of yeasty goodies including pizza dough, crescent rolls, buns, donuts, and more.

Sources:

Buehler, Emily. “Enzymes: The Little Molecules That Bake Bread.” Scientific American Blog Network, 28 Sept. 2012. Web. 21 Feb. 2018.

“History of Yeast.” Dakota Yeast Company. Web. 21 Feb. 2018.

“The History of Yeast.” Breadworld. Fleischmann. 2014. Web. 21 Feb. 2018.

Lawandi, Janice. “The Science Behind Yeast and How It Makes Bread Rise.” Kitchn Apartment Therapy, LLC. 15 Dec. 2015. Web. 21 Feb. 2018.