More than 350 million years ago, warm, shallow seas covered many parts of North America, including much of the Midwest. During this time period, known as the Devonian era, these shallow waters were teaming with salt water marine life. Fish, mussels, crustaceans, and micro-organisms flourished in the region. In addition to the other sea animals, a species of coral formed large colonies in the upper part of Michigan. Millions of years later, this coral hardened into an unusual hexagon patterned stone that represents the state of Michigan today.

More than 350 million years ago, warm, shallow seas covered many parts of North America, including much of the Midwest. During this time period, known as the Devonian era, these shallow waters were teaming with salt water marine life. Fish, mussels, crustaceans, and micro-organisms flourished in the region. In addition to the other sea animals, a species of coral formed large colonies in the upper part of Michigan. Millions of years later, this coral hardened into an unusual hexagon patterned stone that represents the state of Michigan today.

When the ancient seas covered Michigan and surrounding areas, the climate and geology was quite different than it is today. The Great Lakes, the most prominent geographic feature in the state today, were not yet carved out by glacial movement. Instead, the area was subtropical. The conditions were ideal for the growth of colonial coral. These coral colonies grew and spread for more than 60 million years.

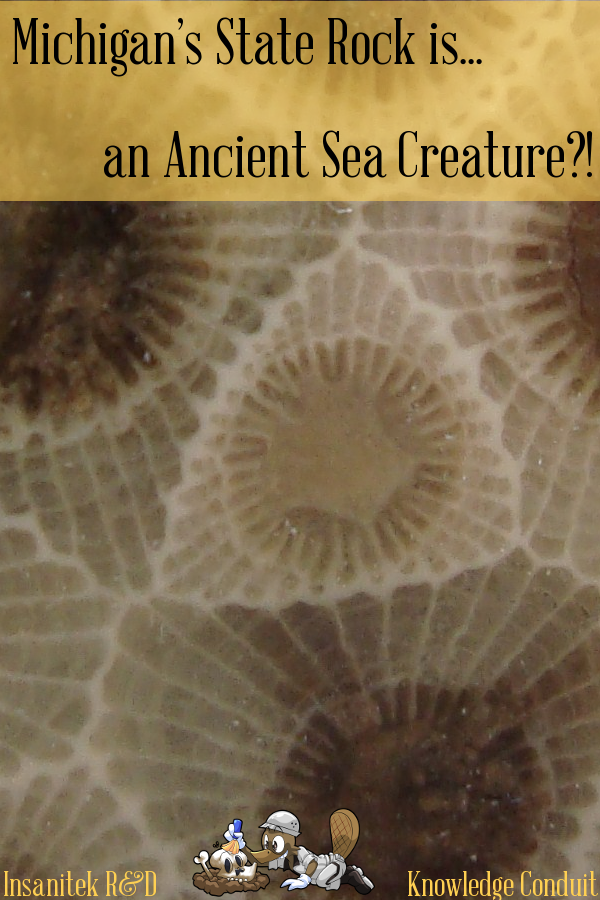

The species of coral in these prehistoric reefs was a type of rugose coral called Hexagonaria percarinata. The massive coral reef is comprised of many, many small coral polyps. Each polyp had a single opening surrounded by hair-like tentacles that helped to filter plankton and other food particles into the mouth of the coral. When these polyps died and solidified, they formed a six-sided, hexagon shaped pattern. The coral reefs were most common in and around the Petoskey and Traverse City areas and Upper Peninsula of Michigan, also there are more colonial corals of the same variety in Coralville, Iowa. When the seas eventually retreated, the coral fossilized and much of it became covered in sandstone and limestone deposits. Over time, the fossilized coral became the Petoskey stone.

The region was drastically different about two million years ago than it was 350 million years ago when the coral was forming. The Pleistocene era of two million years ago brought glacial ice to much of the northern half of North America. The pressure and weight of the ice sped up the petrifaction of the coral fossils. Much later, when the glaciers receded, the land was scoured and scarred by the retreating ice. This action was powerful enough to dig out the Great Lakes, but it also exposed some of the ancient fossilized coral. The fragile coral was broken and crushed, and rolled around in the glacier ice to give us small, roundish, smooth stones. The movement of the glaciers spread the Petoskey stones across the region.

In June of 1965, then-Governor George Romney signed legislation that designated the Petoskey stone as the official state stone of Michigan. The stone was named for the city in the upper part of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula where many of the rocks can be found. But the city was named for an Ottawa Indian.

According to the legends, Antoine Carre, a Frenchman working for John Jacob Astor’s fur trading company in the late 1700s. There, he met and married an Ottawa princess and became an adopted member of the tribe. Carre and his young family were returning to northern Michigan from the Chicago area in the spring of 1787 when, as the group camped near present-day Kalamazoo, his wife gave birth to a son. Carre named his firstborn “Petosegay”, which means “rays of dawn” or “sunbeams of promise.” Much later, the town of Petoskey was named for Carre’s son, although the name was Anglicized. When Governor Romney declared the Petoskey stone the Michigan state stone, Ella Jane Petoskey, the only living descendent of Chief Petosegay, was invited to attend the formal signing of the bill.

Even today, Petoskey stones are easily found on the beaches and inland streams of northern Michigan. In their natural state, Petoskey stones are not polished like the ones in the souvenir shops, so the hexagon pattern is not as prominent. It is easy to pass over a Petoskey stone as an ordinary rock. But upon closer inspection, the six-sided coral formation can be seen.

Petoskey stones are uniquely Michigan. Nowhere else on the planet can these striking, hexagon-patterned rocks be found. The state stone of Michigan is a relic that recalls the geological past of the region, from the subtropical prehistoric seas to the icy Pleistocene glaciers.

Sources:

Teske, Emily. “The Petosky Stone.” Department of Geology. Michigan State University. Web. 22 Jan. 2019.

Tufflemire, Michael. “Prehistoric Michigan Covered by Ancient Seas, Tropical Jungles Before Mitten Formed.” The Rapidian. 8 Apr. 2016. Web. 22 Jan. 2019.

Wilson, Steven E. “The Petoskey Stone.” Department of Environmental Quality. State of Michigan. Web. 22 Jan. 2019.

Share Michigan’s State Rock is an Ancient Sea Creature

|

|

|