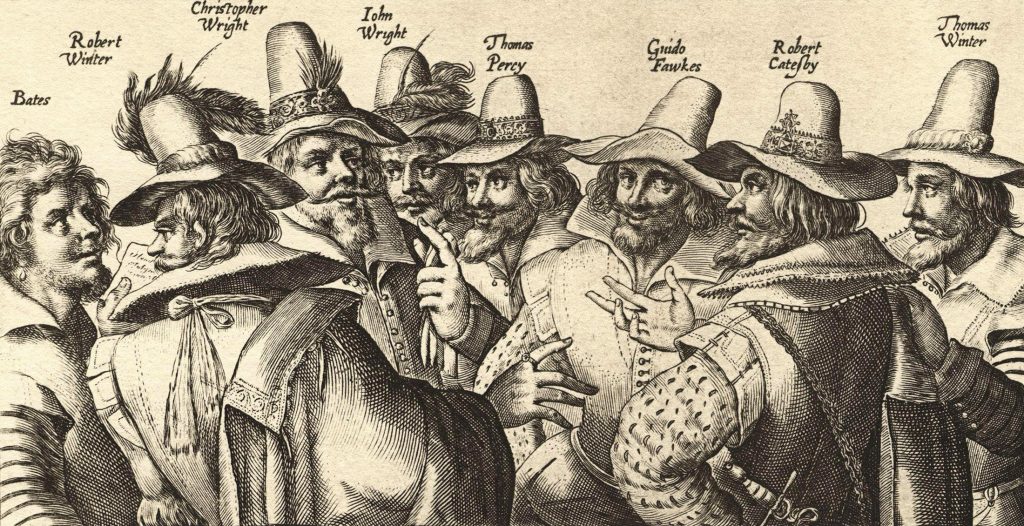

Guy Fawkes Day is a holiday in England and some of the commonwealths that celebrate a failed assassination of King James I. The attempt was both a religious protest as well as a political one. The conspirators plotted to blow up King James on the opening of Parliament, November 5 1605. Tensions were high. Queen Elizabeth the I set the stage in England for the Protestant religion, not a Catholic one. King James I’s mother was Catholic, and it was wrongfully believed that his wife, Anne, was Catholic as well. It was this background that set Guy Fawkes and others to plot for months to kill this king that, presumably, threatened their religion and views of the world.

We know how it turns out, but what people rarely talk about is how this era of explosive energy was made.

Gunpowder, the weapon of choice of Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators, wasn’t intentionally made in a few years. It took a few hundred years of intentional tinkering, and occasionally burning one’s lab to the ground or risking one’s livelihood, to make this weapon of revolution. It is well stated and known that gunpowder began in China sometime before the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618 – 907). We know this because all of the Tang dynasty alchemy books mention saltpetre and it’s preparation (Kelly, 2004).

At first it was used in stunts and displays, a bit of smoke, a little thunder, a lot of noise. Then, as the Chinese grew more bold and confident, they began to use it in psychological warfare against their enemies. A lot of noise and smoke scared away attacker, but the mix was far from refined.

Saltpetre, or potassium nitrate (KNO3), is the mother of gunpowder. It was formed naturally and abundantly in China. Saltpetre is is formed in warm climates by bacterial action during the decomposition of excreta and vegetable refuse. It appears as a white crust on soil in a climate where things decay quickly, but go for long periods without rain. Think marshlands and dung heaps in tunnels for a more picturesque view of what the ancients had to get into to get this precious salt.

They would collect the flowery crystals, wash them of earth and dung, then boiled to refine. At first, this salt was used as just that: salt. It was used to both enhance the flavour of food as well as preserve it. But, alchemist being what they were, began to combine even these common earth elements with other elements to see what would happen.

Eventually they happened upon what they called “fire drug”. Saltpetre, when mixed with a bit of carbon and sulphur and dried with a bit of honey, created a sticky pill that exploded with fire.

But we weren’t quite to big blasts yet.

Yet.

Oh, the creativity of humans where they may be bounds to reach. Sure, this little alchemical pill would create a bit of excitement if it was tossed into fire, but it wasn’t up to the military standards they would soon create. Grinding, mixing, and perfecting away, several alchemist soon moved their work outside for their thatches were set on fire. Curiousness and motivation for more ways to scare off the enemy (as well as entertain with noise and colour), drove the modern fireworks and ancient gunpowder industry.

The early Chinese gunpowder-weapons were akin to giant fireworks in both shape and happening. The fine grained powers, mixed together with a bit of coloured minerals, and put into a cone, provided a raucous noise that would terrorise enemies back to where they invaded from.

But, not for long.

Amazingly enough, the Chinese enemies got over their initial flight response and fought. Soon, the Huns and others invaded and adopted the wonders of gunpowder. This catalyst began it’s spread through the world, but things really get exciting once gunpowder reached the military prowess of King Edward III of England (1312 – 1377). It was King Edward’s obsession with winning and appetite for destruction that breathed life into the gunpowder industry that would take over the world.

This blood-thirsty warmonger reign saw the beginning of the 100 Years War with France, and his son Edward the Black Prince was obsessed with the power of the “gonne” or a rather rudimentary — and quite dangerous — version of a cannon. They were dangerous because if they worked, they tended to be fairly unpredictable in how they would explode and discharge the projectile.

You see, gunpowder was, and is, quite dangerous.

The tradition was at this time to grind the ingredients: saltpetre, sulphur, and carbon. They ground it into a fine powder, nearly a dust. This dust was highly dangerous for the craftsman that ground the powder. Not only because it would get into the air and into the lungs, but one little spark can set their whole operation up in smoke and shrapnel. This fine powder absorbs water fairly quickly, and may not even catch fire. When it did catch, it didn’t burn evenly or predictably, thus making it really difficult to predict how far the projectile will go… if it launches at all.

Often times, the gunners would often transport the barrels of powder to the field, then lay it out dry so it had a better chance of succeeded. But, this is France and England we are talking about. It rains quite a bit, which makes it impractical to transport barrels of gunpowder.

Of course, the price of gunpowder was also extravagant. Saltpetre, the magical ingredient, was not exactly growing on every stone.

But it was growing on outhouse walls.

Through experiments, gunpowder craftsman discovered that the ammonia rich defecation from drunks and animals could be piled up and decomposed in large piles. This would create a huge amount of KNO3 for their war machines. They would store these stinking, festering masses outside the villages, but still near enough to make anyone gag. (Not exactly the best for air pollution, eh?)

This rudimentary manufacture of saltpetre encouraged the craftsman to explore different avenues of processing and storage the powder. The craftsmen did something counter-intuitive that revolutionised gunpowder usage. They added the very thing they always tried to avoid — moisture.

Granted, leave it up to the medieval superstitious practises to make it religious. They would often add something like holy water, wine blessed by a priest, and occasionally the urine of a priest. While they could do that in modern times, they take the far more practical route and just spritz the powder down with water as they grind it, reducing the amount of dust in the air and allowing them to make gunpowder cakes.

These cakes were basically gunpowder that was moistened down, then formed into loaves. These loaves were then left to dry and harden.

Oh, happy accident!

By treating the gunpowder like this, the cakes were less likely to absorb water when in transportation. Then, when the gunners and artillery men were ready, they would crack open the loaves, and put the “corned” gunpowder in the cannons.

Much to the first gunners shock — and death — the explosive power of this new procedure nearly tripled (Kelly, 2004). The fire was able to leap between grains of gunpowder, completely burning the entire batch.

And this was the gunpowder that was used in the Gunpowder Plot against King James I unsuccessfully.

Reference:

Kelly, Jack. 2004. Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards & Pyrotechnics The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. New York.

Gunpowder is a great book that brings history to life while showing you how gunpowder transformed our world from East to West and back again.