Last week we talked about the potential in crowdfunding your research, and there is even some consideration to take here with the bigger picture. Crowdfunding not only gets some of that much-needed financing, but it also helps the broader impacts of your research. While this is a pretty sweet idea, there is one flaw with it:

Most scientists never learn to communicate to the non-scientist.

And, when a majority of the population that could potentially fund you has no idea what you’re on about, it makes it that much harder to get funding. They might be asking, “Why are they asking the questions they are? What significance does this research have? How does it impact the world at large, let alone me? Why should I open my wallet to fund this?”

Good questions to answers if we want funding the traditional way or the modern way. When you do answer these questions fluidly, it makes drawing in funding that much easier.

But talking to the public is different.

Spencer Wells notes in the preface of Pandora’s Seed, a pop-sci book on how our genetics ties into our cultural significance, starts discussing the why behind his book. The why, is of course, rooted in the question “what impact does this research have?” This is a good question for all of us to answer, regardless of what level we are doing research in, or even if it’s just an undergraduate research paper. When we know the value of what we are learning, it takes on a whole new dimension. However, there are two ways to think about this: from the side of the researcher and the side of the public.

Let’s look at the broader impacts from the public perspective.

When I read Wells thoughts on why we should study human evolution in context of genetics and history, my memory was jogged. While teaching a 7th grade section on pH, an exasperated, bored, annoyed student whined, “What is the point of this?” My brain, being rooted in geekiness as it were, immediately thought flusteredly, “Because SCIENCE!”

To fellow scientists, this might be reason enough. Fundamentally, though, I knew that to the public, the tax payers, and those that distribute research funds, you can’t use that answer. You need something more tangible, more meaningful, and something they can understand.

To this student, I showed them videos of what happens to soil when it is either too acidic or too basic. I followed this with more grotesque images of acid burns, a damaged oesophagus from stomach acid burns. The students, by that time, had all gathered around and began discussing the importance of what they were learning, and I didn’t have to say a word of defence.

Unfortunately, it is not always so easy.

Wells points out that the government funds research which may not have immediate interest with the underlying logic that it may be important some day. Tax payers still pay for that research money, so they should be able to get a sense of the possibilities, even if they are intangible at the time. The same holds true with crowdfunding, but the money comes from those that hope or have a little imagination.

This concept had been something I’ve strived to do as I edited my master’s thesis. It wasn’t easy, and I worked on an aspect of meteoric beryllium-10, which can be used to trace soil erosion. Soil erosion is important, so it should have made it easy to explain. However, I still found myself struggling to answer my friends and family who are prodding me to just finish. With something so close to my heart being so difficult to explain, I can imagine how hard it would be to explain they why behind something so esoteric, remote, or specialised that it may have no tangible impact in the near future â luckily I haven’t had to yet.

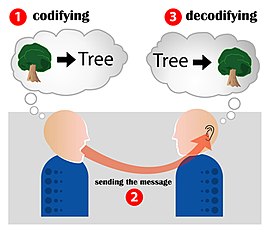

Communication is key.

We’ve always known communication is important, but when finding a little more funding or flexibility in your path, it’s pivotal. We all take it for common knowledge that you must be able to present your ideas in a way that is clear to your audience, but very few of us practise communicating our complex ideas to those outside of our scientific community. Now, as the economy is shifting it’s time to practise. Let’s start now.

We’ve always known communication is important, but when finding a little more funding or flexibility in your path, it’s pivotal. We all take it for common knowledge that you must be able to present your ideas in a way that is clear to your audience, but very few of us practise communicating our complex ideas to those outside of our scientific community. Now, as the economy is shifting it’s time to practise. Let’s start now.

Over to you

Can you explain the importance of your research to a public audience, say a 7th grader and his or her parents, in the comments. I’m truly curious to know some ways that you’d explain it. What methods of technology could you use? Can it be explained simply? The results of this would be useful for all of us so we can get more ideas on public engagement and communication with each other as well.

My personal favourite method has been posters and infographics. I can use a lot of imagery to state what a bunch of data in graph form really can’t. The best part is that images really do tell a good story when I have to run off — inevitably that is when the biggest crowd appears to see what my poster has to say. That broader impact? It takes care of itself.

So, now that I’ve shared my secret weapon, what is yours?