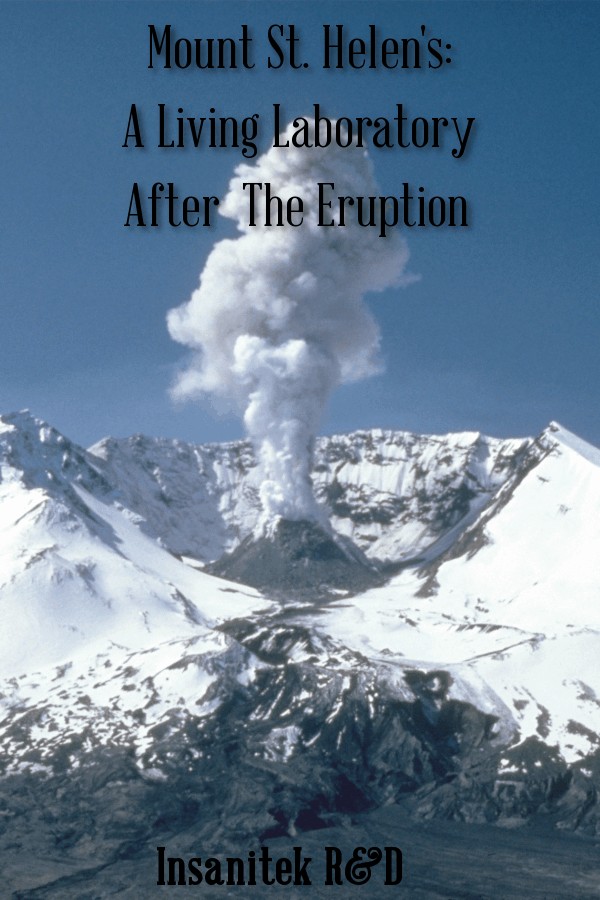

When Mount St. Helens in the cascade mountain range in Washington State erupted on May 18, 1980, the landscape of the mountain was forever changed. The eruption blew off the top 1,000 feet of the volcanic mountain’s summit and sent ash and debris nearly 10,000 feet into the air. The volcano had been rumbling back to life in the months leading up to the massive eruption and geologists had been warning that an eruption was imminent. Why, then, did the volcano kill 57 people?

When Mount St. Helens in the cascade mountain range in Washington State erupted on May 18, 1980, the landscape of the mountain was forever changed. The eruption blew off the top 1,000 feet of the volcanic mountain’s summit and sent ash and debris nearly 10,000 feet into the air. The volcano had been rumbling back to life in the months leading up to the massive eruption and geologists had been warning that an eruption was imminent. Why, then, did the volcano kill 57 people?

Seismologists had observed that the long-dormant mountain appeared to be slowly awakening. Researchers from the University of Washington began monitoring Mount St. Helens in March of 1980. A few weeks later, on March 20, the equipment registered a 4.2-magnitude earthquake underneath the mountain. Yet another quake hit on March 23…this time a 4.0. This triggered a series of small earthquakes…sometimes ten to fifteen quakes per hour…that stretched out over several days and increased in intensity.

Steam rocketed out of Mount St. Helens’ peak on March 27. It seemed that the volcano was releasing some pent-up pressure. The steam plume shot more than 6,000 feet in the air and created a 250-foot wide hole in the summit. After that, the rumbling stopped and the mountain became quiet. The reprieve was short-lived. The mountain shook again in early May, and over the next ten days, geologists noted that the north side of the mountain was bulging, reaching out nearly 450 feet. This was a clear sign that the magma was rising within Mount St. Helens.

With all these warning signs that Mount St. Helens was preparing to blow its top, geologists and seismologists had ample time to warn the public and order evacuations. No one should have been on the mountain when it erupted, yet many people were.

One reason why Mount St. Helens was so deadly was that geologists and seismologists lacked the highly-accurate, state-of-the-art equipment in 1980 that they have today. Their equipment was good, but it was still limited. They were not able to predict the size of the eruption, the blast zone, or the force with any accuracy.

Mount St. Helens had not erupted in the last one hundred years. The last known eruption was in 1857 and, although it was significant event, the eruption only produced gas and ash. It did not cause widespread destruction or alter the face of the mountain. Many scientists believed that the 1980 eruption would follow suit. When the mountain finally did erupt in May of 1980, the amount of energy that was released by the blast surprised geologists.

One of the biggest shocks with the eruption was to sheer size of the area that was involved. Scientists, working with the U.S. government, had established a danger zone, but in hindsight, that danger zone was much too small…only about three miles. All but three of the people killed in the Mount St. Helens blast were well outside the danger zone that had been set up, so they probably assumed they were safe. Ironically, there was a proposal sitting on the governor’s desk that called for the expansion of the danger zone. But it was the weekend, so the governor didn’t see the proposal until Monday morning, the day after the eruption.

The loss of life would have been much higher had the eruption not occurred on a Sunday morning. That’s because local officials made the decision to exempt people involved in the logging industry, an important part in the local economy, from the mandatory evacuation of the danger zone. If the eruption had occurred on a work day, the mountain would have claimed the lives of hundreds of loggers. The blast was so powerful that it snapped over millions of trees…some was big as twenty feet in diameter.

A few people that perished in the Mount St. Helens eruption died from stubbornness. Among them was a man named Harry Truman…not the former president of the United State. This Truman was a reclusive mountain man who lived with a bevy of cats in a wooded lodge close to the summit of Mount St. Helens. Truman defiantly refused to leave his home of more than fifty years and was determined to ride out the eruption in his lodge. His stubbornness inspired other mountain dwellers to also refuse to follow evacuation orders. Unfortunately, when the blast occurred, it sent a huge landslide…the largest one in history…down the side of Mount St. Helens toward Spirit Lake. Truman, his lodge, and his cats were buried under more than 200 feet of mud, ash, and debris. His remains were never found.

Out of all the destruction and death caused by the eruption of Mount St. Helens there emerged some good. Geologists and seismologists learned a tremendous amount from studying the eruption, the lead up to it, and the aftermath. With that information, they are now much better equipped to predict future volcanic activity in the Cascades. Additionally, Mount St. Helens served as a living laboratory. Biologists and wildlife experts were able to observe how plants and animals respond to natural disasters such as this. They were amazed at how the mountain healed itself from the wound of the eruption, with only minor scars.

Sources:

Bagley, Mary. “Mount St. Helens Eruption: Facts & Information.” LiveScience, 16 Oct. 2018. Web. 31 Dec. 2018.

Clynne, Michael, David W. Ramsey, and Edward W. Wolfe. “Pre-1980 Eruptive History of Mount St. Helens, Washington.” U.S. Geological Survey, 2005. Web. 31 Dec. 2018.

Worrall, Simon. “Mistakes Led to Needless Deaths From Worst Volcanic Blast.” National Geographic Magazine, National Geographic Society, 21 Mar. 2016. Web. 31 Dec 2018.