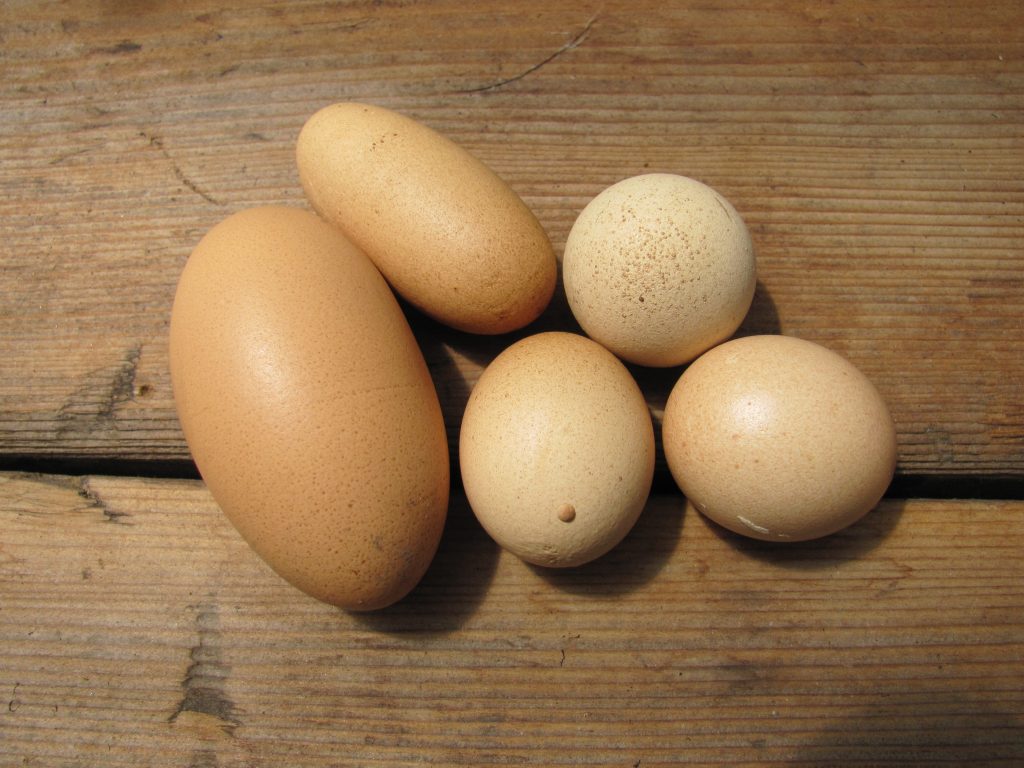

The funny thing about bird eggs is that they are not all egg-shaped! Some birds lay round eggs and some lay elongated eggs. Some egg-shaped eggs are more pointy – more egg-treme – than others. Scientists have conducted several studies and the general conclusion is that several different factors impact the shape of a bird’s egg, including the size of the clutch, the maturity level of the chick when it hatches, the location of the nest, and the calcium content of the shells. All of these affect the roll of the egg, but the most recent study of egg morphology has shown that one other key factor that contributes to the shape of the eggshell…the flight of the bird. No yolk!

For most of us, the only bird egg we see on a regular basis is the chicken egg, which gives us the most common shape. It is the shape that we have adopted for our plastic Easter eggs, after all. Aristotle, the renowned Greek philosopher, possibly contemplating his impending breakfast, famously wondered why eggs are shaped they way they are…in an asymmetrical ovoid. He theorized (wrongly, we may add) that the shape of an egg denoted the sex of the chick. He believed that the rounder eggs hatched male chicks while the longer, pointier eggs produced female chicks. It is when we move away from chicken eggs and begin observing the eggs of other birds that we witness Aristotle’s theory fall apart. Owl and ostrich eggs, for example, are round. Hummingbird eggs are more elliptical in shape. And sandpiper eggs are somewhat pointy on one end. With Aristotle’s theory shot down, this left the egg shell shape a favorite mystery of biologists for hundreds of years.

There has been no shortage of theories explaining egg morphology. Some focus on the average size of the clutch per bird species. The idea is that the bird has a limited nest size, based on its construction ability, availability of resources, and location, and it needs to maximize that space. Therefore, the shape of the eggs has evolved to take advantage of the available nest size. There are, however, too many exceptions to this rule to make it totally plausible. The bald eagle, for example, creates the largest nest of any bird. Their enormous nests can be five feet in diameter, or larger, meaning there is plenty of space for a supersized family. Not so. The bald eagle’s clutch rarely exceeds three eggs and the eggs themselves, while comparatively large, are not so big that three of them will fill a five-foot area. On the contrary, bald eagle eggs are about three inches long.

Another interesting idea is that the egg’s shape is indicative of the location of the nest. Scientists have observed that the more asymmetrical an egg is, the tighter it rolls. This led to the theory that bird who build their nests in higher locations, such as the tops of trees or on cliffs, produce eggs with a tighter turning radius…nature’s way of making sure the eggs don’t roll off the cliff. When we look at the egg of the murre, this theory makes sense. Murres lay their eggs high on precarious cliffs and their eggs are among the most asymmetrical in shape. But this theory doesn’t fit across the bird spectrum. Sandpipers lay eggs that are nearly as asymmetrical as the murre, yet they make their nests on the ground. On the other hand, the hawk owl’s egg is the most spherical of all bird eggs. Round like balls, these eggs could easily roll in any direction so we would expect, based on the location theory, that hawk owls also make their nests on the ground. But this is incorrect. This species of bird typically builds their nests on the top of dead spruce trees, typically 7 to 30+ feet above the ground.

As all the prevailing theories explaining egg morphology were disproven, biologists appeared to be no closer to cracking the mystery. Until recently. According to a New York Times article, a team of researchers from across the globe, headed by lead researcher Dr. Mary Caswell Stoddard of Princeton University, began photographing and measuring bird eggs. They combed though museum collections and initiated the help of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley University. In all, the team acquired more than 49,000 photographs of bird eggs representing 1,400 bird species and the majority of bird orders. The images were scanned into a computer program that they created. This program plotted many key traits of the bird and looked for connections between birds with similar traits and the egg shapes. When the results were in, the researchers arrived at a surprising finding. The most consistent factor relating bird trait to egg shape was flight.

The egg morphology was strongly connected to the shape of the bird’s wing, which is the biggest factor in the bird’s ability to fly. The role of the egg is to nurture the baby chick, but it also helps to prepare the chick for life outside the shell. Birds that excel at flight need lean, sleek bodies, therefore their eggs are narrower. The study showed that the types of birds hatched from pointier eggs, like those of the murre and the sandpiper, have wings designed for more sustained flight, allowing the bird to fly further distances. As explained by one of the researchers, Dr. Joseph Tobias of the Imperial College London, “Variation across species in the size and shape of their eggs is not simply random but is instead related to differences in ecology, particularly the extent to which each species is designed for strong and streamlined flight.” Dr. Lakshminarayanan Mahadevan, a professor of organismic and evolutionary biology and physics at Harvard University and the author of the study, noted, “Perhaps, evolutionarily, birds stumbled upon this very natural, geometric solution, which is to increase the ellipticity and asymmetry of their eggs.”

Because the researchers had access to museum collections, they were able to include fossilized egg and bird data into their study. Stoddard observed that looking into the past and examining the evolution of birds, bird flight, and egg morphology, has provided support for the team’s findings. She noted, “The idea that powered flight and pointy eggs evolved around the same time is particularly intriguing.”

More research needs to be conducted, of course, to ultimately prove the link between flight and egg morphology, but this study has shed light on avian evolution as well as on research methodology itself. As Stoddard explained, “In something as familiar and common as a bird egg, we are still discovering new truths.” She added, “We can challenge old assumptions.”

Sources:

Crespi, Sarah and Jia You. “Why Do Eggs Have So Many Shapes” Cracking the Mystery of Egg Shape, 22 June 2017, Web. 17 Jan. 2018.

McRae, Mike. “We’ve Finally Worked Out Why Bird Eggs are Egg-Shaped.” ScienceAlert. 23 June 2017. Web. 17 Jan. 2018.

“The Surprising Link Between Egg Shape and Bird Flight.” National Geographic, National Geographic Society, 22 June 2017. Web. 17 Jan. 2018.

Yin, Steph. “Why Do Bird Eggs Have Different Shapes? Look at the Wings”. The New York Times. 22 June 2017. Web. 17 Jan. 2018.