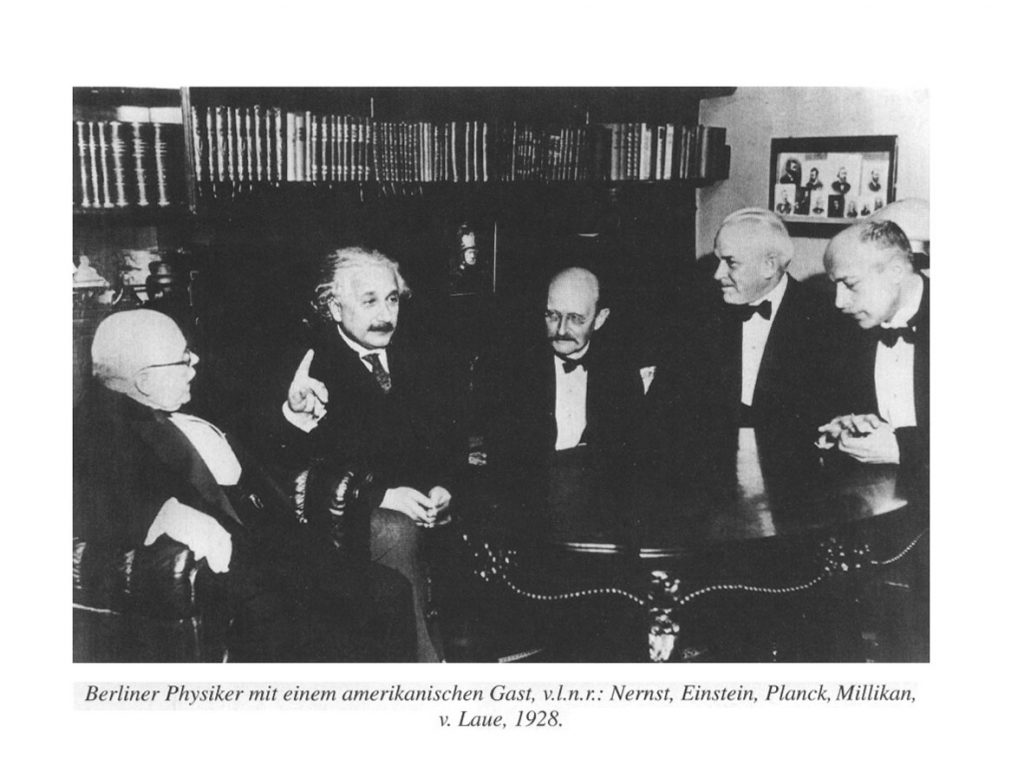

Albert Einstein wrote in 1948, “Even in these times of ours when political passion and brute force hang like swords over the anguished heads of men, that even in such times there is being held high and undimmed the standard of our ideal search for the truth. This ideal, a bond forever uniting scientists in all times and in all places, was realised with rare completeness in Max Planck.” Einstein further described Planck’s 1900 discovery “as the basis of all 20th century research in physics and has almost entirely conditioned it’s development ever since. Without it’s discovery, it would not have been possible to establish a workable theory of atoms and molecules and the energetic process which govern their transformation.

A slow genius As a child, Planck showed aptitude for everything he tried. His favourites were languages, mathematics, Bible study, and music. He relished his studies. It was noted that he was quite near the top of his class, but he was not a genius. However, he was slow to say he knew something until he understood all the nuances in the field up to the most recent advancements

This sort of mentality channelled Planck’s thoughts to physics as his thesis. When his advisor tried to persuade him to leave the field as “everything has already been discovered,” Planck stayed the course claiming he’d be just as happy to deepen our understanding of the world. This approach, combined with his fascination of atoms, lead Planck to investigating the relationships that tie physics and the atoms together for a lifetime. Thus, Max Planck was able to uncover the fields of thermodynamics, black-body radiation, and working with Albert Einstein, able to deepen quantum theory.

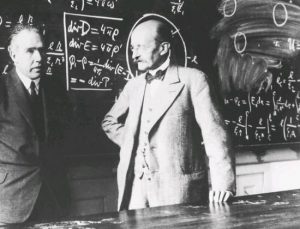

A Brilliant Approach to Knowledge Niels Bohr and Max Planck Planck taught physics as a whole system, fully developed and fully integrated with other fields such as chemistry. While it wasn’t a popular position at the time, he favoured the notion that chemistry and physics were not separate because that is not how things exist in nature.

Planck believed in this integrated approach so steadily that he got into a written combat with the Positivists

Amusingly enough, Planck also encouraged questions of all levels while teaching. He believed that all outcome of all questions were good. Brown

Voice of Reason between the World Wars Max Planck came into his own during World War I, then became more popular and respected not just in his field, but also in a larger political sphere. He had a love of country, but also a calm demeanor that people respected and looked up to. The fact that he was the father of quantum physics and developed the field of thermodynamics gave Planck more street cred in the eyes of the German people as well as his colleagues.

As the Wiemar republic wobbled and Germany rebuilt after WWI, Planck sought a way to keep the expensive enterprise of science going without relying on the wobbly Wiemar government. He joined forces with the chemist Fritz Haber and Adolf von Harnack to found the Notgemeinschaft, a private society that could fundraiser around the world then dispense grants to the scientists at home. The project was a qualified success, raising 8 million marks and winning contributions from a lot of companies Notgemeinschaft was no longer active.

Max Planck was dedicated to science in a way that saved him from a lot of drama in his life. His first wife died from tuberculous 19 years after they were married, leaving Planck a single father to four children. Although Planck remarried later on, his family quickly fell apart again when one of his daughters died during childbirth, his eldest son was killed in action in WWI, and his youngest son was taken prisoner in WWI. It was only Planck’s optimism and love of science that kept him moving forward during his darkest times.

Science and The Nazi Regime During the first 74 years of his life, Max Planck loved his Prussian countrymen, loved the culture, and loved science. Although Planck viewed the Nazi party with ambivalence at first, he eventually grew to detest the Nazi party. He viewed them as irrational, and even went so far as to promote Einstein in his speeches — a jab to the Nazi party that viewed Planck as a national treasure for his brilliance

Planck went further in his writings, reflecting on his own role, and other’s, for what happened during the Nazi regime:

“Under no circumstance can there be in this domain [one’s own conscience] the slightest moral compromise, the slightest moral justification for the smallest deviation. He who violates this commandment, perhaps in the endeavour to gain some momentary worldly advantage, by deliberately and knowingly shutting his eyes to the proper evaluation of the true situation, is like a spendthrift who thoughtlessly squanders away his wealth, and who must inevitably suffer, sooner or later, the grave consequences of his foolhardiness.” — Planck, in the closing paragraph of Phantom Problems

Despite of all his optimism, Max Planck clearly struggled with the culture being divided and torn apart around him. In the end the Nazi regime even murdered his son, Erwin, who operated actively against the Nazi regime. At age 87, Max Planck pled for his son’s life by writing a short, simple letter directly to Hitler

Planck left a scientific legacy that can be summed up with what his friends called the Planck Principle:

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

{21495:3DEJDKAM};{21495:FX3T5XMG};{21495:9P964ARU};{21495:9P964ARU};{21495:FX3T5XMG};{21495:FX3T5XMG},{21495:9P964ARU};{21495:LUI7TF7A};{21495:6Q2TQ7Z8}

apa

default

asc

0

6726